English Translation1 of Sapporo District Court Ruling in Raporo Ainu Nation’s Salmon Fishing Rights Lawsuit

Translated by Michael J. Ioannides

Published by AinuToday on May 5, 2025

All rights reserved.

Cite as:

Ioannides, Michael J. 2025. “English Translation of Sapporo District Court Ruling in Raporo Ainu Nation’s Salmon Fishing Rights Lawsuit.” AinuToday. https://ainutoday.com/english-translation-of-sapporo-district-court-ruling-in-raporo-ainu-nations-salmon-fishing-rights-lawsuit/.

Table of Contents

Click the links below to quickly navigate to each section. To return to the top of the page, click the gray button in the lower right-hand corner of your screen.

Case Caption (Judgment)

Summary of Ruling (It is hereby judged that)

Facts and Reasons of the case

Section 4: Arguments of the Parties

Issue 1: About the Legality of this Lawsuit

Defendants’ Arguments

(1) On the Motion for Confirmation of Fishing Rights

(2) On the Motion for Confirmation of Invalidation

Plaintiffs’ Arguments

(1) On the Motion for Confirmation of Fishing Rights

(2) On the Motion for Confirmation of Invalidation

Issue 2: About whether the Plaintiffs have fishing rights

Plaintiffs’ Arguments

(1) The nature of the right to catch salmon as claimed by the Plaintiffs

The Collectivity of Rights

The Inherency of Rights

(a) Ainu History

(b) Ainu Culture, Spiritual Traditions, and Philosophy

(c) Summary

(2) Details of the Fishing Rights in Question

(3) Legal Basis for the Fishing Rights in Question

A: Treaties, et cetera

(b) International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

(c) International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights

(d) International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination

(e) Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

B: Ainu Policy Promotion Act

C: Constitutional Guarantee

(a) Article 14

(b) Article 29

(c) Article 13

(d) Article 20

D: Customary Law

E: Reason

(4) Conclusion

Defendants’ Arguments

(1) On the Plaintiffs’ Claims Regarding Customary Law

(2) On the Plaintiffs’ Claims Regarding Treaties

(3) On the Plaintiffs’ Claims Regarding Collective Rights

(4) On the Plaintiffs’ Claims Regarding the Constitution

(5) On the Plaintiffs’ Claims Based on Reason

(6) On the Validity of Article 28 of the Act on the Protection of Marine Resources

(7) Conclusion

Section 5: Judgment of the Court

1. Recent Developments Regarding the Ainu

(1) Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

(2) Resolution Calling for the Ainu to be Recognized as an Indigenous People

(3) Establishment of the Advisory Council on Ainu Policy

(4) Passage of the Ainu Policy Promotion Act

2. Ainu Livelihoods, Traditions, Culture, et cetera

(1) Historical Background of the Ainu

(2) The Role of Salmon Fishing in Ainu Livelihoods, Traditions, Culture, et cetera

3. Restrictions on Salmon Fishing in Inland Waters under Current Law

4. Nature and Content of the Fishing Rights Claimed by the Plaintiffs

5. On Issue 1

(1) On the Motion for Confirmation of Fishing Rights

(2) On the Motion for Confirmation of Invalidation

6. On Issue 2

(1) On the Right to Enjoyment of the Ainu’s unique culture

(2) On whether or not the Plaintiffs possess the fishing rights claimed in this case

(3) On the validity of Article 28 of the Act on the Protection of Marine Resources

7. Conclusion

Appendix 1: Catalog of Fishing Rights

Appendix 2: Excerpts of Related Laws, et cetera

April 18, 2024 Judgment Delivered to Clerk of Court on Same Day

Case No. 22 of 2020 (Civil Litigation) Motion for Confirmation of Salmon Fishing Rights

Date of Conclusion of Oral Arguments: February 1, 2024

JUDGMENT

Plaintiffs: Raporo Ainu Nation

Address: Urahoro Town Health and Welfare Center 8-1 Kitamachi, Urahoro Town, Tokachi District, Hokkaido.

Acting Chairman of the Board of Directors: Satoshi Tanno2

Plaintiffs’ Counsel: Morihiro Ichikawa, et al.

Defendant 1: Japan

Address: 1-1-1 Kasumigaseki, Chiyoda Ward, Tokyo

Minister of Justice: Ryuji Koizumi

Defense Counsel: Koji Yamazaki, et al. & Hiroyuki Kajimoto, et al.

Defendant 2: Hokkaido

Address: Kita 3 Sanjo Nishi 6 Chome, Chuo Ward, Sapporo

Governor: Naomichi Suzuki

Defense Counsel: Koji Yamazaki, et al. & Ryosuke Sato, et al.

IT IS HEREBY JUDGED THAT

1. The Motion for Confirmation that Article 28 of the Act on the Protection of Marine Resources is invalid insofar as it concerns the Plaintiffs’ list of claimed fishing rights is DISMISSED.

2. The Plaintiffs’ remaining claims are DISMISSED.

3. Court costs shall be borne by the Plaintiffs.

FACTS AND REASONS OF THE CASE

Section 1: Demands.

1. Confirm that the Plaintiffs possess the fishing rights listed on the attached catalog of fishing rights.

2. Thereby confirm that Article 28 of the Act on the Protection of Marine Resources (Law No. 313, 1951) is invalid insofar as it concerns the fishery described in the Plaintiffs’ attached catalog of fishing rights.

Section 2: Case Overview.

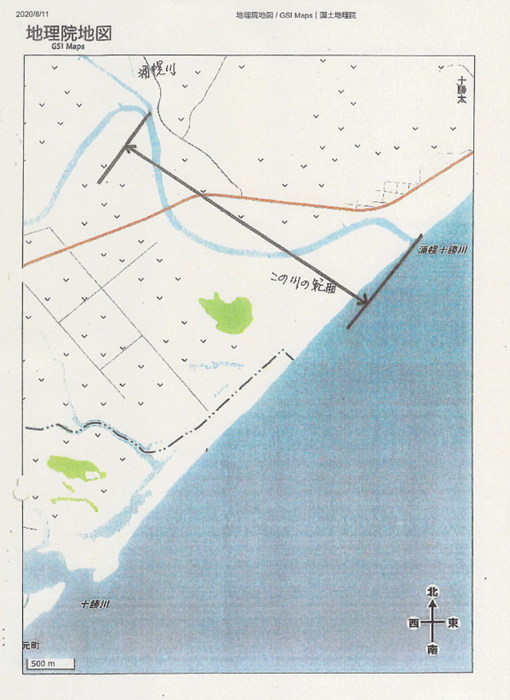

In this case, the Plaintiffs are an organization composed of Ainu residing in the town of Urahoro, Tokachi District, Hokkaido, and, as an association without the legal capacity to rights, the Plaintiffs have filed a complaint against the Defendants, alleging that the Plaintiffs have an inherent right as an Ainu group to fish for salmon in inland waters (i.e., bodies of water above sea level; see the Fishery Act, Article 60, Paragraph 5, Clause 5), specifically the rights listed in the attached catalog of fishing rights (hereinafter referred to as “the fishing rights in this case”). As a substantive class action, the Plaintiffs seek confirmation that they possess the fishing rights in this case. This action is hereinafter referred to as the “Motion for Confirmation of Fishing Rights.” The Plaintiffs also seek, as a substantive class action, confirmation that Article 28 of the Act on the Protection of Marine Resources, which prohibits, in principle, the harvesting of salmon in inland waters, is invalid under Article 4, Sentence 2 of the Administrative Litigation Act, insofar as it concerns the fishery described in the attached catalog of fishing rights (hereinafter referred to as “the fishery in question”). This action is hereinafter referred to as the “Motion for Confirmation of Invalidation.”

1. Assumed Facts (facts that are not in dispute between the Parties or can be readily ascertained from the evidence or pleadings).

(1) Relevant Laws and Regulations.

The relevant laws and regulations are listed in Appendix 2.

The abbreviations in Appendix 2 are used in this text.

(2) About the Plaintiffs.

A: The Plaintiffs are an organization comprised of Ainu residing in the town of Urahoro, Tokachi District, Hokkaido, and is an association without the legal capacity to hold rights.

B: On July 20, 2020, the Plaintiffs changed their name from the Urahoro Ainu Association to Raporo Ainu Nation and amended their bylaws to include the aim of acquiring Ainu Indigenous rights, beginning with salmon fishing rights, to establish the dignity of the Indigenous Ainu people, to overcome all barriers based on race and ethnicity, to improve their social status, and to preserve, transmit, and develop their culture (Exhibit A-1(i), (ii)).

Section 3: Points at Issue

1. Issues prior to these Proceedings.

About the legality of this lawsuit (Issue 1).

2. Issues of these Proceedings.

Whether the Plaintiffs possess the fishing rights in this case and whether Article 28 of the Act on the Protection of Marine Resources is invalid insofar as the fishery in question is concerned (Issue 2).

Section 4: Arguments of the Parties

Issue 1: About the legality of this lawsuit.

(Defendants’ Arguments)

As argued below, this lawsuit is unlawful and should be dismissed.

(1) On the Motion for Confirmation of Fishing Rights.

A: Absence of a Legal Dispute.

The target of a judgment in a civil case, including administrative cases, as stated in Article 3(1) of the Court Act, is a “legal dispute,” which is limited to (1) disputes over the existence or non-existence of material rights and obligations or a legal relationship between the parties and (2) disputes which can be conclusively resolved by the application of laws and statutes (see Supreme Court of Japan, 1976 (final civil appeal) No. 749, Third Petty Bench decision of April 7, 1976, Civil Division Vol. 35, No. 3, paragraph 334; Supreme Court of Japan, 1990 (final administrative appeal) No. 192, Second Petty Bench decision of April 19, 1991, Civil Division Vol. 45, No. 3, p. 518).

Because, generally speaking, fishing by private persons in rivers and streams (inland waters) is understood as a legal relationship under public law (administrative law) in which rivers and streams are used as public property (natural public property), the fishing rights in dispute in this case should be understood as a claim to the right to use a river or steam (an inland water) that is public property.

In this sense, it is recognized that the use of public property is subject to legal restrictions from the perspective of the management of public properties, and a request to use public properties for which these types of restrictions have been recognized means a request for non-application or termination of said restrictions as a legal relationship under public law. Therefore, whether this is permissible should be decided based on the interpretation and application of laws and statutes related to said restrictions. In addition, according to Article 28 of the Act on the Protection of Marine Resources, the harvesting of salmon from inland waters, including rivers and streams, is prohibited in principle, and exceptions to this regulation are limited to the cases provided in the text of that same article. The Plaintiffs have not been granted a fishing license for inland waters of any kind, and in order for the Plaintiffs to catch salmon in inland waters by gill net, the only option, provided in Article 52 of the Act on the Protection of Marine Resources, is to obtain permission from the Governor of Hokkaido to lift the prohibition provided in Article 28 (hereinafter referred to as a “Special Harvest Permit”). Because this law does not confer on the Plaintiffs any rights, the fishing rights that the Plaintiffs seek to confirm have no basis in substantive law. Furthermore, the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) itself is not legally binding for member states, nor are the collective rights being claimed by the Plaintiffs based on UNDRIP established under international customary law. Therefore, it must be acknowledged that the fishing right that the Plaintiffs seek to confirm— that is, the right to allow the non-application or termination of regulations on the use of public property as a legal relationship under public law—has no basis in positive law.

In light of the above, since the fishing right claimed by the Plaintiffs is not a right or legal interest with any actual legal basis (lack of requirement in (1) above) the dispute concerning the existence or non-existence of the fishing right in question is not one that can be resolved in Court through the application of substantive law (lack of requirement in (2) above). Therefore, the action to confirm the fishing rights in this case is unlawful because it does not constitute a “legal dispute”.

B: Lack of standing to be the subject of a “motion for the confirmation of a legal relationship under public law” (Administrative Litigation Act, Article 4, Sentence 2).

Generally, in a motion for confirmation in a civil suit, the necessary condition for legal action is that the confirmation has a benefit, i.e., that the Plaintiff’s rights or legal status are presently uncertain, and as a means of eliminating this uncertainty, a judgment is made on the existence or non-existence of the legal relationship between the Plaintiff and Defendant based on rights or legal status, and the matter subject to confirmation must be valid and relevant. And since this is a motion for confirmation in civil litigation, defined by the Administrative Litigation Act (Article 4, Sentence 2) as a “motion for confirmation of a legal relationship under public law,” the above should equally apply.

As for this case, the subject of this Motion for Confirmation of Fishing Rights is not something that can be derived from the interpretation of existing laws and statutes, as stated in A above, and cannot be recognized as a right under substantive law unless the National Diet passes new legislation to enable the Plaintiffs to exercise the fishing rights in this case. In this way, the fishing rights in this case are not concrete rights under substantive law, and the question of their existence or non-existence is not a suitable subject for the Court to determine.

Therefore, the Motion for Confirmation of Fishing Rights in this case is unlawful because it lacks standing to be the subject of a motion for confirmation.

(2) On the Motion for Confirmation of Invalidation.

A: Absence of a Legal Dispute.

Since laws and statutes generally establish only abstract norms, unless the statute itself has a specific and concrete content, or the content of the statute itself is abstract but its direct effect is to affect the specific rights and obligations of an individual, a motion challenging the legality or validity of the statute itself does not constitute a “legal dispute” in that it is not a dispute concerning the existence or non-existence of specific rights and obligations or a legal relationship between the parties. If we apply this to the present case, Article 28 of the Act on the Protection of Marine Resources is a general and abstract provision, subject to the exceptions prescribed in the proviso of said article, because it is a general and abstract provision, with no particular or specific party in mind, stipulating that anadromous fish, including salmon, shall not be harvested from inland waters. Additionally, while Article 28 is rather abstract in the way it stipulates its various provisions, in actuality, it is intended only to apply to specific persons, without the possibility of being applied to other parties. Therefore, it cannot be said that the article directly affects the specific rights and obligations of individuals.

According to the above, the case is unlawful because the Motion for Confirmation of Invalidation leaves aside the specific dispute between the Plaintiffs and the Defendants, and whether or not the Article 28 of the Act on the Protection of Marine Resources is invalid is not a “legal dispute.”

B: Lack of standing to be the subject of a “motion for the confirmation of a legal relationship under public law” (Administrative Litigation Act, Article 4, sentence 2).

It is generally understood that the validity or invalidity of a law or statute cannot be the subject of a motion for confirmation. Additionally, if we follow the wording of Article 4 of the Administrative Litigation Act, which in its second sentence uses the phrase “a motion for the confirmation of a legal relationship under public law”; along with the principle given by the Code of Civil Procedure that we ought to confirm presently-existing rights and legal relationships; in essence, it is understood that it is necessary to establish a claim based on the Plaintiff’s current rights, obligations, and legal status as the subject of the motion for confirmation. If the Motion for Confirmation of Fishing Rights in this case is legal, this motion, which seeks direct confirmation of the present rights claimed by the Plaintiffs, is more valid and appropriate than the Motion for Confirmation of Invalidation, in terms of its subject matter.

Therefore, since there are other appropriate subjects of confirmation to remove the uncertainty of the rights or legal status claimed by the Plaintiffs, the Motion for Confirmation of Invalidation should be said to lack the benefit and standing to be the subject of a motion for confirmation.

As stated above, the Motion for Confirmation of Invalidation is unlawful because it lacks the benefit of confirmation.

(Plaintiffs’ Arguments)

(1) On the Motion for Confirmation of Fishing Rights.

A: Presence of a Legal Dispute.

The fishing rights claimed by the Plaintiffs are not provided for in statutory law, but exist as inherent rights of Indigenous peoples, as described in Appendix 2: Plaintiffs’ Claims. It is also clear that the Supreme Court decision cited by the Defendants is completely different from the circumstances of this case. Therefore, the Defendants’ argument has no merit. The Motion for Confirmation of Fishing Rights in this case seeks confirmation as to whether or not the Plaintiffs have the right to catch salmon as a precondition for a concrete dispute as to whether or not the Plaintiffs will be criminally punished for catching salmon. Therefore, it is a dispute concerning a concrete right or obligation, and one that can be conclusively resolved through the application of the law. The Motion for Confirmation of Fishing Rights in the case constitutes a “legal dispute.”

B: Presence of standing to be the subject of a motion for confirmation under the Administrative Litigation Act (Article 4, sentence 2).

Under the current interpretation of the law, if the Plaintiffs harvest salmon without a permit, they may be subject to penalties, and the Plaintiffs’ fishing rights in this case are threatened by the government’s actions. Before they find themselves in a situation in which they are subject to criminal investigation and criminal prosecution, it is the Plaintiffs’ interest to clarify that, because they possess the fishing rights in question, their harvesting of salmon is not prohibited by the Fishery Act or other related laws and regulations and they will not be penalized for fishing for salmon without a statutory permit, which is a sufficient benefit.

Therefore, the Motion for Confirmation of Fishing Rights has standing to be the subject of a motion for confirmation.

(2) On the Motion for Confirmation of Invalidation.

We contest it.

Issue 2: About whether the Plaintiffs have fishing rights and whether Article 28 of the Act on the Protection of Marine Resources is invalid as far as the fishery in question is concerned.

(Plaintiffs’ Arguments)

(1) The nature of the right to catch salmon as claimed by the Plaintiffs (an inherent right as a collective).

A: The salmon fishing right claimed by the Plaintiffs is a collective right of the Ainu as an Indigenous people. The collective in question refers not to the Ainu people as a whole, but to the group commonly referred to as kotan that fished for salmon. In addition, because the Plaintiffs are a group comprised of Ainu, most of the Plaintiffs are descendants of ancestors who lived in several kotan (mainly Tokachibuto and Tokachikotan) in and around present-day Urahoro Town, especially in the estuary of the former Tokachi River (present-day Urahoro-Tokachi River). In 2020, the Plaintiffs changed their name to Raporo Ainu Nation and amended their bylaws to include the aim of “acquiring Ainu Indigenous rights, beginning with salmon fishing rights.” In this way, the Plaintiffs are an organization acting as an Ainu collective seeking rights.

B: The Collectivity of Rights.

The existence of collective Ainu rights is supported by the history of the Ainu, especially the kotan, the group that historically had monopolistic and exclusive fishing rights in certain river basins. According to anthropologist Hitoshi Watanabe’s monograph, “The Ainu Ecosystem,” kotan ranged from one to more than ten households (but usually no more than ten households) and were distributed along rivers at intervals of around four to eight kilometers. Kotan were sited in locations that provided adequate drinking water, along with hunting and fishing grounds. Salmon spawning grounds were particularly important, and kotan were usually located on fluvial terraces3 near established salmon spawning grounds. Cooperative production of these resources was related to the size of the kotan, with three or fewer households comprising a single cooperative productive unit. Since the kotan in the former Tokachi River estuary were essentially small-scale kotan with few households, it can be assumed that the kotan had a cooperative relationship. The ancestors of the members of the Plaintiffs’ organization were thus engaged in a cooperative relationship with other kotan, which brings together the Plaintiffs as a class in the present day.

Furthermore, according to the monograph cited above, the kotan exercised monopolistic and exclusive control over “salmon spawning grounds,” and communally levied sanctions on intruders who violated this control. In addition, according to the same monograph, in situations where several local groups4 (i.e., small social groups with common ties to a region) were located adjacent to each other on the same river course, they formed a group that was distinguished from other groups based on their territory in the river and its catchment basin, which prohibited unauthorized exploitation of any resource by outsiders throughout all four seasons. Such river groups were established as a regional unit through the relationship between the kamuy (gods) of the area and the Ainu who lived there, and the river group was considered the largest unit of people who shared common ties to a given region, via the kamuy. In this way, the Plaintiffs are the present-day successors of a river group(kotan) who share common ties to the kamuy of the former Tokachi River estuary, and have inherited monopolistic and exclusive fishing and hunting rights to the former Tokachi River estuary. Furthermore, since kotan were formed as groups around salmon spawning grounds, they essentially have monopolistic and exclusive authority over the harvest of salmon.

C: The Inherency of Rights.

The rights claimed by the Plaintiffs as an Ainu collective are inherent rights as an Indigenous people, the same as the collective rights of Indigenous peoples around the world. Inherent rights mean rights that were not recognized for the first time by the Constitution, laws, et cetera.

Paragraph 7 of the Preamble to the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples clearly states that “the inherent rights of Indigenous peoples derive from their political, economic, and social structures, and from their culture, spiritual traditions, history, and philosophy.” The Plaintiffs’ right to catch salmon is precisely this type of inherent right, as it was established based on “their culture, spiritual traditions, history, and philosophy” since before recorded history (which began in the 7th century with Japanese records).

(a) Ainu History.

As stated in B above, the Ainu historically organized themselves into groups called kotan which had monopolistic and exclusive fishing rights in particular river basins, and even during the period of direct control by the Shogunate at the end of the Edo period, Ezochi was still regarded as a “foreign land” and the Ainu as “people living in foreign lands,” which were not under the Shogunate’s direct control.

Additionally, at the end of the Edo period, although the Ainu were being exploited for their labor by local contractors, they also engaged in hunting and fishing as members of a group that was considered “self-employed.” The term “self-employed” refers to the fact that they, as members of a group that hunted and fished in the territory owned by a kotan, possessed ownership rights over the resources harvested. The Ainu then traded these harvested salmon, along with marine products and animal pelts obtained via hunting, with merchants.

Therefore, the Ainu historically formed groups called kotan and engaged in monopolistic and exclusive fishing and hunting as groups, making a living not only from hunting and fishing, but also through trade. This long-standing historical fact establishes the right to catch salmon as an Ainu right, which is considered an inherent right.

(b) Ainu Culture, Spiritual Traditions, and Philosophy.

The Ainu have, for example, constructed their own unique culture centered on salmon, including a spiritual world associated with salmon, salmon-related cooking methods, and salmon-related clothing production. Furthermore, as described in the monograph cited in B above, through salmon fishing, they formulated a spiritual worldview based on common kinship and geographical ties5 to the kamuy of their river basin.

In this way, Ainu culture, spiritual traditions, and philosophy also establish the foundation of the inherent nature of their salmon fishing rights. In connection to this point, in Paragraph 7 of General Comment 23 of the United Nations Human Rights Committee,6 which provides the unifying interpretation of Article 27 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, states that

“with respect to the exercise of the cultural rights guaranteed in Article 27, the committee finds that culture expresses itself in various forms, in particular in the form of a distinctive way of life linked to the use of resources.”

In other words, culture is a way of life tied to resource use. As a way of life, this right “also includes… the right to engage in traditional activities such as fishing or hunting,” and culture is expressed through Indigenous ways of life not limited to “traditional activities.” Ainu groups made a living by drying and processing salmon for trade, in addition to catching salmon for their own consumption—this is culture as a way of life.

This argument of the Defendants does not guarantee the right to culture stipulated in Article 27 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights in the first place, but is based on Japan’s own view which rejects the guarantee in Article 27, and is not internationally accepted.

Furthermore, Paragraph 6.2 of General Comment 23 recognizes that the cultural rights of Indigenous peoples also apply collectively. This is because, in Indigenous societies, the rights to own, manage, and use land and resources are considered to belong to the group, not to individuals, which are aspects that cannot be reduced to individual rights. Thus, the United Nations Human Rights Committee recognizes that the rights of individuals belonging to minorities may be exercised collectively, and the minority group itself is protected as a precondition for guaranteeing the rights of individuals belonging to minorities, thereby recognizing that these rights apply to collectives.

D: Summary.

As argued above, the salmon fishing rights claimed by the Plaintiffs were formulated by Ainu history and derived from their culture, spiritual traditions, and philosophy, and are inherent rights of the Ainu as a collective.

(2) Details of the Fishing Rights in Question.

The details of the fishing rights in question in this case are described in the attached Appendix 1: Catalog of Fishing Rights, but the fishing method is gill net fishing using a boat with an outboard motor. Article 52 of the Regulations imposes the unreasonable requirement that special harvest permits be granted for the “transmission and preservation of traditional ceremonies and fishing methods related to fishing in inland waters or for the dissemination and promotion of knowledge concerning these matters.” Presently, when the Plaintiffs harvest salmon under a special harvest permit, they are instructed to use a log canoe and a unique Ainu harpoon called a marek, and they are not allowed to sell the salmon they catch. However, the Ainu continued fishing for salmon throughout the Edo period until it was illegally banned during the Meiji period, and if it had not been banned, they would of course still be fishing for salmon today using new technology, such as fishing boats with onboard motors, nylon nets, et cetera. In fact, it has been confirmed that gill-net fishing was popular during the Edo period by the identification of netting needles among repatriated grave goods.7 In light of this, hunting and fishing using new technology should be recognized as a right.

Therefore, the salmon fishing rights claimed by the Plaintiffs can be summarized as above.

(3) Legal Basis for the Fishing Rights in Question.

A: Treaties, et cetera.

(a) In our country, treaties ratified by the national government have domestic effect by promulgation alone, and take precedence over other laws (Constitution of Japan, Article 98, Paragraph 2). Laws must therefore be enacted, interpreted, and applied in conformity with treaties, and the Court must reject their application insofar as they conflict with treaties. Each of the treaties and declarations that Japan has ratified and agreed to (the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, and the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples) guarantee the fishing rights claimed by the Plaintiffs, who are a minority, and any law or regulation is invalid insofar as it does not recognize these rights.

(b) International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Article 27 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights guarantees the rights of minorities to enjoy their culture, stipulating that

“in countries where ethnic, religious, or linguistic minorities exist, persons belonging to such minorities shall not be denied the right to enjoy their own culture, to believe and practice their own religion, or to use their own language, with other members of their group.”

Human rights covenants are conventionally overseen by a committee, which carries out the duty of interpreting the covenant as an institutional body so that the domestic implementation of the covenant is not left to the arbitrary will of each country. Therefore, when interpreting the convention, the summary findings, general comments, and opinions of the covenant committee should be considered authoritative interpretations, and State Parties should give them due consideration in fulfilling the obligation of good faith compliance with the covenant.

In General Comment 23 on the interpretation of Article 27 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the United Nations Human Rights Committee recognizes the collective right of Indigenous peoples to use resources, stating that

“the rights protected by Article 27 are individual rights, but such rights also depend on the ability of ethnic minority groups to maintain their own culture, language, or religion. There is therefore a need for positive measures by State Parties to protect the identities of ethnic minorities and the rights of members of such minorities to enjoy and develop their culture and language and to practice their religion together with other members of their ethnic group” (Paragraph 6.2)

and that

“certain aspects of the individual rights protected by this Article, such as the enjoyment of a particular culture, may reside in a way of life closely related to a territory or the use of its resources. This is particularly true for persons belonging to Indigenous communities that constitute minority groups” (Paragraph 3.2).

Moreover, the same General Comment guarantees the fishing and hunting rights of Indigenous peoples, which includes economic activities, stating that,

“with regard to the exercise of the cultural rights protected by Article 27, the Committee considers that culture expresses itself in various forms, but particularly in the form of a distinctive way of life linked to resource use. These rights include the right to engage in traditional activities such as fishing or hunting or the right to live in a reservation protected by law. The enjoyment of such rights requires positive legal protection measures to ensure the effective participation of members of minority groups in decisions affecting them” (Paragraph 7).

In addition, the same General Comment states that “the rights associated with Article 27 impose specific obligations on State Parties” (Paragraph 9), and as a State Party, our country is obligated to guarantee the Plaintiffs’ “rights to engage in traditional activities such as hunting and fishing,” including economic activities.

(c) International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

Article 15, Paragraph 1(a) of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights guarantees all persons “the right to participate in cultural life,” and in 2009, the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights issued General Comment 21 in regard to this right.

General Comment 21 points out that the cultural rights guaranteed by Article 15 are essential for the maintenance of human dignity and positive social interaction between individuals and communities in a diverse and multicultural world (Paragraph 1), and that this right is characterized substantively as “freedom” and requires the state to take positive measures as well as demanding non-intervention in cultural practices, et cetera (Paragraph 6).

The same General Comment also notes that the rights guaranteed by Article 15 are collective rights that can be exercised individually, in conjunction with others, or as a community or group (Paragraphs 7 and 9), and that, for Indigenous peoples in particular, these rights are either highly communal or are expressed and exercised only as a community (Paragraph 36).

With respect to Indigenous peoples in particular, the same General Comment notes that Article 15 includes their ancestral “rights to land, territories, and resources” and requires State Parties to “take measures to recognize and protect the rights of Indigenous peoples to own, develop, manage, and use their communal lands, territories, and resources” (Paragraph 36) to prevent the decline of Indigenous peoples’ distinctive ways of life (including their means of subsistence), the loss of their natural resources, and, ultimately, the loss of their cultural identities.

(d) International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination.

i) Article 1, Paragraph 1 of the International Convention on the Elimination of All forms of Racial Discrimination provides that

“the term ‘racial discrimination’ as used in the Covenant means any distinction, exclusion, restriction, or preference on the basis on race, skin color, descent, or ethnic or tribal origin, which has the purpose or effect of preventing or impairing the recognition, enjoyment, or exercise of fundamental freedoms on equal footing in political, economic, social, cultural, or any other sphere of public life.”

Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs also states that being Ainu is included in the category of “ethnic or tribal origin” as defined in the Covenant.

The above “discrimination” includes not only “purposeful” acts that impair the enjoyment and exercise of fundamental freedoms on equal footing, but also indirect discrimination which has the “effect” of impairing these freedoms.

Moreover, Article 5 of the International Convention on the Elimination of All forms of Racial Discrimination provides that

“in accordance with the fundamental obligations set forth in Article 2, State Parties shall undertake to prohibit and eliminate all forms of racial discrimination and the guarantee the right of all persons to equality before the law, without discrimination on the basis of race, skin color, ethnicity, or tribal origin, in the enjoyment of the following rights, in particular,”

which includes “d) other civil rights, including…(v) the right to own property, alone or jointly with others.” In other words, the Covenant requires State Parties to prohibit and eliminate all forms of discrimination against Indigenous peoples’ “right to own property, alone or jointly with others” and to guarantee equality before the law for this right. Moreover, the Covenant recognizes that the concept of property rights for Indigenous peoples is principally a communal and collective concept, and that this right applies not only to individuals belonging to Indigenous peoples, but collectively, as a right with collective characteristics.

ii) In 1997, the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination issued General Recommendation 23 with respect to Indigenous peoples, which calls on State Parties to

“recognize and respect the unique cultures, histories, languages, and livelihoods of Indigenous peoples as enriching the cultural identity of the nation, and promote their preservation,”

as well as to

“recognize and protect the rights of Indigenous peoples to own, develop, manage, and use their communal lands and territories and to take steps to return lands and territories traditionally owned by Indigenous peoples where such lands and territories have been stolen or where such lands and territories have been occupied or used by others without their free and informed consent,”

and that, with respect to this right to restoration, when restoration is not possible for practical reasons, just, impartial, and prompt compensation should be granted, taking the form of land or territory whenever possible.

In addition, the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination has repeatedly advised our country to protect the rights of the Indigenous Ainu to their lands and resources.

iii) As stated above, Article 5 of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination recognizes the Plaintiffs’ rights to salmon resources that they, as an Indigenous group, have historically had. As a signatory, our country is obligated to protect those rights and to return them if they have been taken away. Because the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination takes precedence over other laws, in accordance with Article 98, Paragraph 2 of the Constitution, any law to the contrary is invalid. Moreover, even if the automatic enforceability of the Covenant is not immediately recognized, its contents are realized through the interpretation of Article 14 of the Constitution, and any law or regulation contrary to the Covenant are invalid because they are contrary to said Article. In other words, to the extent that the Act on the Protection of Marine Resources prohibits salmon fishing by the Indigenous Plaintiffs, it is invalid and contrary to the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, as well as the Constitution.

(e) Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

The Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples—adopted in 2007 with our country’s support—guarantees the rights of Indigenous peoples to their lands, territories, and resources in Articles 25 and 26, stipulating that “states must grant legal recognition and protection to these lands, territories, and resources.” It also states in Article 2 that

“Indigenous peoples and individuals who are Indigenous…have the right not to be subjected to any discrimination in the exercise of their rights on the basis of their origin or identity as Indigenous peoples.”

The Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples has a high degree of legitimacy in terms of its content (which is based on the principles of international human rights law) and its procedures (which were developed with the active involvement of Indigenous peoples), and was adopted by an overwhelming majority of the United Nations General Assembly, making it an authoritative United Nations human rights document with the support of the international community.

B: Ainu Policy Promotion Act.

Article 4 of the Ainu Policy Promotion Act prohibits discrimination against the Ainu people and the infringement of their rights and interests.

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination have direct effect in Japan and take precedence over national laws. Article 15 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights provides for the basic right to freedom, and has a judicially normative and overriding effect in Japan. Moreover, since our country agreed to the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, it is obligated to reflect the Declaration’s contents in its national policy and to realize them through the Ainu Policy Promotion Act. Therefore, the interpretation of Article 4 of the Ainu Policy Promotion Act regarding the prohibition of discrimination against the Ainu people and the protection of their rights and interests must be based on the aforementioned treaties, at the very least.

Prohibiting the Plaintiffs, an Indigenous group, from salmon fishing is an act of discrimination that deprives the Indigenous Ainu of their rights to resources guaranteed by the above treaties and endangers the preservation of their culture, beliefs, and identity. Doing so infringes the rights that the Ainu possess and exercise as an Indigenous People, and is an illegal act in violation of Article 4 of the Ainu Policy Promotion Act.

C: Constitutional Guarantee.

(a) Article 14 of the Constitution.

As noted above, the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination provides that depriving Indigenous peoples of the right to own, manage, and use their lands and resources constitutes unlawful discrimination, and mandates that State Parties shall not engage in such discrimination. The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination has national legal force in Japan and takes precedence over other laws and statutes. Moreover, if we take into account the call of General Recommendation 23 to State Parties (noted above), Article 14 of the Constitution should be understood to guarantee the Indigenous Ainu people the right to harvest salmon, a resource in the areas they traditionally have inhabited.

Therefore, Article 28 of the Act on the Protection of Marine Resources and the Hokkaido Fisheries Adjustment Regulations are unconstitutional and invalid insofar as they prohibit the Plaintiffs from salmon fishing, being in violation of Article 14 of the Constitution.

(b) Article 29 of the Constitution.

It is obvious that the Ainu right to fish for salmon is a property right under customary law and in principle, and is guaranteed under Article 29 of the Constitution.

However, this right is not only a property right, but also a spiritual right that is a precondition for their cultural identity as an Indigenous people, as identified in the aforementioned treaties. It is, furthermore, a right to recognized and protected by the International Convention on The Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination as a right that has been taken away by settlers and the governments due to discrimination against Indigenous peoples.

In light of our country’s ratification of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (noted above), the Constitution guarantees to Indigenous Ainu groups the collective rights to resources.

(c) Article 13 of the Constitution.

The right to the pursuit of happiness guaranteed by Article 13 of the Constitution, in accordance with the concept of “respect for the individual” provided in its first sentence, is understood to be a right that comprehensively guarantees the rights and freedoms that are important in asserting oneself as an autonomous person (a basic human right). “Respect for the individual” is a concept that disavows totalitarianism at the expense of the individual, not one that prevents communality in Indigenous cultures. Indigenous peoples’ communal use of their inherited lands and resources is integral to their culture and spirituality, and should be constitutionally respected. For Ainu, salmon are not only food, but are also extremely important to their culture, forming the political, economic, social, and cultural basis of the Indigenous Ainu people, as well as the spiritual basis of their beliefs and worldview. Salmon constitute an important foundation of Ainu culture, including fishing methods, cooking, et cetera, and have shaped the Ainu’s religious and spiritual world.

Therefore, for the Plaintiffs, too, the right to fish for salmon is necessary for their personal survival and to maintain and enjoy their people’s unique culture. Moreover, because awareness of their ethnicity is the basis of their identity, it is impossible to maintain and enjoy their unique culture without existing as an ethnic group.

As stated above, Indigenous peoples’ right to enjoy their inherited resources is essential for the preservation of their means of livelihood, the maintenance of their way of life, the economic survival of their communities, and their connections to future generations, as well as being a precondition for the cultural identity of the individuals that belong to these groups. Such a right is guaranteed by Article 13 of the Constitution.

(d) Article 20 of the Constitution.

For Ainu, the act of salmon fishing is strongly marked by religious elements involving a connection with and gratitude toward the kamuy (gods), not only in the ceremonies and fishing methods themselves, but throughout the entire process, beginning with the preparatory stage. Salmon fishing is at the heart of religious ceremonies (such as the ashirichepnomi, which thanks the gods for a bountiful catch and Ainu prosperity), and if salmon fishing is banned, then the very meaning of such ceremonies will be lost.

Therefore, it is clear that Ainu salmon fishing is conducted with an intention of reverence and awe based in a conviction of the existence of a supernatural or more-than-human essence (i.e., the Absolute, the Creator, the Supreme Being; e.g., God, Buddha, the soul, et cetera). The right to do so, even under current law, is a right that ought to be protected under Article 20, Paragraph 1 of the Constitution, which protects the freedom of religious acts of connecting with and praying to the gods through ancestral lands and the resources of those lands.

D: Customary Law.

Customs that are not contrary to public order or good morals have the same force and effect as the law in matters that are not recognized or prescribed by law or statute, and customary law that has reasonable content in the constitutional realm and is observed with normative awareness can be one source of constitutional law that supplements codified law. Therefore, such a custom not only has “the same force and effect as the law” under Article 3 of the Act on General Rules for Application of Laws (hereinafter, the General Rules Act), but also has force and effect as a constitutional right.

During the Edo Period, the right of an Ainu group to harvest salmon was recognized and controlled by Ainu custom. In other words, the Ainu groups for whom catching salmon was permitted, along with the extent of the permissible location, timeframe, and means of capture, were all defined by Ainu culture. This custom was established as a norm that bound Ainu groups together, not only when settling disputes among themselves (charanke), but also when the Matsumae clan settled disputes over hunting and fishing rights. Therefore, the Plaintiffs’ customary right to catch salmon has been handed down since the Edo Period at the latest, and continues to have binding force in the present day.

Moreover, it is clear that such a custom is not contrary to public order or good morals as referred to in Article 3 of the General Rules Act, since it is neither detrimental to the interests of the state or society, nor contrary to general moral principles.

In addition, as stated above, the fact that Article 28 of the Act on the Protection of Marine Resources does not recognize any right to catch salmon is contrary to the provisions of international law guaranteeing the rights of Indigenous peoples, and the Plaintiffs’ right to catch salmon therefore qualifies as a matter not provided for in the law.

Therefore, the Plaintiffs’ right to fish for salmon is based on customary law under the General Rules Act, and is also a constitutional right.

E: Reason.

As has been argued thus far, it is clear that the Plaintiffs’ salmon fishing rights are recognized by treaties, the constitution, and customary law. Yet, even if these norms are not held to be the basis for the Plaintiffs’ salmon fishing rights, this is simply because these rights are not provided for in laws and statutes, and the Plaintiffs’ rights to fish for salmon must be interpreted as a right recognized based on reason.

“Reason” refers to general and universal principles that serve justice. In light of this, and in addition to the previous arguments, the total prohibition of the Plaintiffs’ salmon fishing rights by the Japanese government in 1883, without any reasonable justification and without any substitute measures being taken, was an injustice of the highest order committed by the state. Moreover, because the aforementioned treaties, et cetera, can be said to express universal principles that transcend national borders, and because “reason” is recognized as this type of universal principle of justice, the Plaintiffs’ fishing rights ought to be recognized.

(4) Conclusion.

As argued above, the Plaintiffs possess the fishing rights claimed in this case and Article 28 of the Act on the Protection of Marine Resources is invalid as far as the fishery in question is concerned.

(Defendant’s Arguments)

(1) On the Plaintiffs’ Claims Regarding Customary Law.

A: Based on the principles of legal administration, even if we allow for the establishment of customary law as a source of administrative law with respect to the basis for rights and freedoms of private individuals who are subject to the exercise of administrative authority, such establishment must not be contrary to existing law.

Moreover, the Plaintiffs’ customary practice of catching salmon in specific rivers and inland waters without prohibition or punishment under the Fishery Act, the Act on the Protection of Marine Resources, or the Regulations, is clearly in conflict with the wording and intent of Article 28 of the Act on the Protection of Marine Resources, which prohibits, in principle, the harvesting of salmon from rivers and other inland waters in order to maintain salmon resources, in light of the characteristics of salmon and the fact that harvesting salmon who have returned to a river before they have spawned will prevent the next generation of fish from that river from reproducing and deplete salmon stocks.

Therefore, since the customary practice claimed by the Plaintiffs is contrary to Article 28 of the Act on the Protection of Marine Resources, there is no way for it to be established as customary law as a source of administrative law.

B: Moreover, neither (1) Article 27 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, nor (2) the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous peoples, which the Plaintiffs cite, obligate State Parties to guarantee rights, such as the salmon fishing rights claimed by the Plaintiffs.

In other words, (1) Article 27 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights only stipulates the rights of minorities to enjoy their own culture and does not stipulate rights to land or resources, as is clear from its wording. It does not obligate State Parties to guarantee the right to catch salmon beyond the scope of the Act on the Protection of Marine Resources as claimed by the Plaintiffs. Given that the General Comment of the United Nations Human Rights Committee that the Plaintiffs rely on as the basis of their claim is not legally binding on State Parties, including Japan, and does not obligate them to follow it, it is understood that each State Party is allowed to decide individually how to interpret and implement the provisions of the Covenant in light of the General Comment. Additionally, in our country, Article 17 of the Ainu Policy Promotion Act simplifies the procedures for harvesting salmon for the purpose of preserving and transmitting Ainu ceremonies or disseminating knowledge and raising awareness about Ainu ceremonies, compared to the general procedure of applying for a special harvest permit, so the right of Ainu persons to enjoy their culture is properly guaranteed, and domestic policy has been implemented with the intent of Article 27 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights in mind.

Furthermore, (2) the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples is a resolution adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 2007 based on Article 10 of the UN Charter, and is merely a recommendation, not a legally binding obligation on UN member states. Even in light of these treaties, it cannot be said that the prohibition on salmon fishing in rivers and other inland waters provided in Article 28 of the Act on the Protection of Marine Resources does not apply to the Ainu’s right to catch salmon.

C: Summary.

In addition, as described further below, Article 28 of the Act on the Protection of Marine Resources cannot be found to be invalid, insofar as it applies to the plaintiffs, and in violation of Article 14, Paragraph 1 of the Constitution or the respective treaties cited by the Plaintiffs. The salmon fishing rights claimed by the Plaintiffs cannot be said to “relate to matters not provided for in laws or statutes” as prescribed by Article 3 of the General Rules Act, nor are they even recognized as rights under customary law.

Therefore, the Plaintiffs’ argument regarding customary law is without merit.

(2) On the Plaintiffs’ Claims Regarding Treaties.

A: Article 27 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

As stated above, Article 27 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights does not obligate State Parties to guarantee the salmon fishing rights claimed by the Plaintiffs as an ethnic minority, and the right of Ainu persons to enjoy their own culture is adequately protected in our country under the same Article.

Therefore, the Plaintiffs’ argument regarding the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights is without merit.

B: Article 15 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

The wording of Article 15 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which recognizes the “rights of all persons to participate in cultural life,” indicates that the provision only stipulates the rights of individuals to participate in cultural life and does not obligate State Parties to guarantee the “fishing rights” of “ethnic minorities” as a “group.” It is obvious that the Article does not obligate State Parties to guarantee the salmon fishing rights claimed by the Plaintiffs. Moreover, domestic policy pertaining to Ainu persons conforms to the intent of the provisions of Article 15, Paragraph 1 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

On this point, the Plaintiffs rely on the General Comment of the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, but in view of the legal effect of General Comments, et cetera, this does not affect the above conclusion, that said Article does not obligate State Parties to guarantee “fishing rights” to “groups” called “ethnic minorities.”

Therefore, the Plaintiffs’ argument regarding the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights is without merit.

C: International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination.

In order to protect and cultivate salmon stocks and maintain salmon resources in the future, Article 28 of the Act on the Protection of Marine Resources prohibits, in principle, the harvesting of salmon from rivers and other inland waters. In this way, the Article does not violate the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination because it does not discriminate against Ainu persons or “hinder or impair” the “recognition, enjoyment, or exercise” of their “human rights or fundamental freedoms on equal footing” (International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, Article 1, Paragraph 1). Moreover, it is clear that the Convention does not obligate State Parties to guarantee salmon fishing rights claimed by the Plaintiffs beyond the framework provided in the regulations of the Act on the Protection of Marine Resources.

While the Plaintiffs rely on the General Recommendation of the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, in view of the legal effect of General Comments (and Recommendations), this clearly does not affect the above conclusion, that the Convention does not obligate State Parties to guarantee salmon fishing rights beyond the framework provided in regulations of the Act on the Protection of Marine Resources.

Therefore, the Plaintiffs’ argument regarding the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination is without merit.

(3) On the Plaintiffs’ Claims Regarding Collective Rights and International Customary Law.

Collective rights are not established rights under international customary law.

A: The content of the Indigenous rights that the Plaintiffs claim to have been established as international customary law is understood to be similar to the provisions of Article 26 of the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. However, as stated above, as a resolution of the UN General Assembly, the Declaration is merely a recommendation, and is not legally binding on UN member states.

B: In addition, under general international law, the requirements for the establishment of international customary law are (1) that an international practice has arisen through the accumulation of certain acts of states (general practice), and (2) that this practice has come to be recognized as legally obligatory or justified by several states (legal certainty).

Furthermore, (A) at the time of the adoption of the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, our country stated that

(i) “although the Declaration stipulates some rights as collective rights, the concept of collective human rights is not widely recognized or accepted in all countries…We believe that the rights set forth in the Declaration should not be detrimental to the human rights of other individuals. Therefore, the Government of Japan considers that the ownership and other use rights to land and other property provided for in the Declaration, including how they should be exercised, shall be subject to reasonable restrictions in order to coordinate with and protect the rights of third parties and the public interest.

The United Kingdom stated that (ii) “the concept of collective human rights is not recognized under international law.” A statement by Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Mexico, Thailand, and other countries similarly held that

(iii) “the right to land and resources provided in Article 26 of the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples does not grant Indigenous peoples the monopolistic or exclusive right to own and use them, and the manner in which such rights are exercised shall be interpreted under national law and shall not infringe the rights of third parties who already have legal rights.

Moreover, (B) at the third meeting of the UN General Assembly on November 19, 2018, Romania, speaking on behalf of Bulgaria, France, and Slovakia, stated (i) that it does not “recognize the collective rights of any group based on origin, culture, language, or belief.” (ii) In light of the United Kingdom’s statements to the same effect in (A)(ii) above, it cannot be said that that Indigenous peoples’ “collective rights” (including the rights claimed by the Plaintiffs based on Article 26 on the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples) are recognized by international society in (1) general practice or (2) legal certainty. In this way, such “collective rights” cannot be recognized as established rights under international customary law.

C: Therefore, the Plaintiffs’ argument regarding collective rights under international customary law is without merit.

(4) On the Plaintiffs’ Claims Regarding the Constitution.

A: Article 14, Paragraph 1 of the Constitution.

It is well-established under case law that Article 14, Paragraph 1 of the Constitution stipulates equality under the law and that this provision should be interpreted as prohibiting unreasonably discriminatory treatment (see Supreme Court of Japan, 1962 (final administrative appeal) No. 1472, Grand Bench decision of May 27, 1964, Civil Division Vol. 18, No. 4, p. 676, et cetera). Thus, equality under the law as stipulated in Article 14, Paragraph 1 is a relative right that is established in comparison to others, and the determination of whether or not something conforms to this standard is based on (1) whether there is differential treatment, and if there is, (2) whether it is justified.

However, Article 28 of the Act on the Protection of Marine Resources does not permit the harvesting of salmon in inland waters such as rivers, with certain exceptions, so it cannot be said that the Article itself makes any distinction in the rights or legal status of Ainu persons and non-Ainu persons with respect to harvesting salmon in inland waters such as rivers. In this way, Article 28 of the Act on the Protection of Marine Resources does not provide for unreasonably discriminatory treatment between Ainu and non-Ainu persons, does not violate Article 14, Paragraph 1 of the Constitution, and does not guarantee the salmon fishing rights claimed by the Plaintiffs.

Therefore, the Plaintiffs’ argument regarding Article 14, Paragraph 1 of the Constitution is without merit.

B: Article 29, Article 13, and Article 20, Paragraph 1 of the Constitution.

Even if we allow for the possibility that salmon fishing by Ainu persons could be guaranteed as a right under the provisions of Article 29, Article 13, and Article 20, Paragraph 1 of the Constitution, this right would not be absolutely unconstrained, but would be subject to restrictions based on public interest (as defined under Articles 12, 13, 22, and 29 of the Constitution). Considering that the regulations of the Act on the Protection of Marine Resources also apply to the harvesting activities of Ainu persons, the salmon fishing rights claimed by the Plaintiffs are not immediately guaranteed by the provisions of Article 29, Article 13, and Article 20, Paragraph 1 of the Constitution.

Therefore, the Plaintiffs’ argument regarding Article 29, Article 13, and Article 20, Paragraph 1 of the Constitution is without merit.

(5) On the Plaintiffs’ Claims Based on Reason.

Reason as a basis for administrative law refers to principles that are considered to be naturally applicable even if no written legal source exists, such as the principles of good faith, prohibition on abuse of rights, proportionality, and equality. In situations in which the principles of administrative law are deemed valid, it should not generally be permissible to alter a conclusion drawn from the law based on reason.

Moreover, as mentioned above, Article 28 of the Act on the Protection of Marine Resources does not permit the harvesting of salmon in inland waters such as rivers, with prescribed exceptions, and, as explained below, given that said Article cannot be found to be invalid and in violation of the Constitution and the respective treaties put forth by the Plaintiffs insofar as it applies to them, there is no way to surmise that reason conflicts with the content of Article 28 of the Act on the Protection of Marine Resources, and the fishing rights in question should not be recognized based on reason.

Therefore, the Plaintiffs’ argument regarding reason is without merit.

(6) On the Validity of Article 28 of the Act on the Protection of Marine Resources.

A: The Act on the Protection of Marine Resources is intended to aid in the development of fisheries by protecting and cultivating fishery resources and maintaining their effectiveness into the future (Article 1), and stipulates that “salmon and other anadromous fish shall not be harvested from inland waters” (Article 28, main clause). In light of the characteristics of salmon and the importance of salmon resources to our country, the harvesting of salmon—the most important of the anadromous fishes—from inland waters such as rivers is prohibited in principle, without being limited to specific areas or targeted species.8

That is to say, salmon are fish with a characteristic life cycle, in which they spawn in rivers and hatch as fry, which then make a long journey downstream to the sea, where they mature into adult fish, and after about four years, they return to the rivers where they were born to spawn and end their lives. If salmon that, having this characteristic life cycle, have returned to a river are harvested before they have spawned, this will prevent the next generation of fish from that river from reproducing and deplete salmon stocks. Moreover, because salmon possess these characteristics and are genetically linked to particular regions, it is infeasible to achieve the objective of salmon resource protection by prohibiting their harvest only in certain areas or for certain targeted species.9

In light of the above, in order to prevent the harvest of parent fish before they have spawned and avoid depleting salmon stocks, the necessity of the prohibition, in principle, on harvesting salmon in inland waters ought to be recognized.

B: In this way, while the main text of Article 28 of the Act on the Protection of Marine Resources prohibits the harvesting of salmon in inland waters, and as a result, all harvesting of salmon in inland waters, including the harvesting of salmon for the purpose of transmitting Ainu ceremonies, et cetera, is prohibited in principle, the provisions of said Article allow, as an exception, the harvest of salmon from inland waters with a license or permission from the prefectural governor.

In Hokkaido, salmon harvesting in inland waters can be conducted by obtaining a special harvest permit from the governor in accordance with Article 52 of the Regulations, if the purpose is the transmission or preservation of traditional ceremonies or fishing methods or the dissemination of knowledge and education related to these matters, and under Article 17 of the Ainu Policy Promotion Act. Moreover, when Ainu persons obtain a permit to harvest salmon in inland waters for the purpose of transmitting or preserving ceremonies, et cetera, or for the dissemination of knowledge and education relating to ceremonies, et cetera, the procedures are simpler than the general procedures for obtaining special harvest permit.

C: As stated above, the system of laws pertaining to the harvesting of salmon in inland waters, including Article 28 of the Act on the Protection of Marine Resources, is necessary and reasonable, and takes into consideration the right of Ainu persons to enjoy their culture related to salmon fishing, while at the same time providing the necessary regulations to avoid depleting salmon stocks.

Therefore, it cannot be said that Article 28 of the Act on the Protection of Marine Resources is invalid as far as the fishery in question is concerned.

(7) Conclusion.

Based on the above, each of the Plaintiffs’ claims should be dismissed because they all lack merit.

Section 5: Judgment of the Court.

1. Recent Developments Regarding the Ainu.

(1) Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

On September 13, 2007, the UN General Assembly adopted the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, with the Japanese government casting a yellow vote (a salient fact). However, the Japanese government made the following points as to its position on the draft resolution:

A: Although some rights are defined as collective rights in this Declaration, the concept of collective human rights is not widely recognized and accepted in international law.

B: The Japanese government, bearing in mind the ideas towards which this Declaration is directed, believes that individuals who constitute Indigenous peoples enjoy the rights set forth in the Declaration and that, with respect to some rights, these individuals may exercise their rights together with other individuals who have the same rights.

C: The Japanese government believes that the rights provided for this in the Declaration shall not be detrimental to the human rights of other individuals. We also recognize that, with respect to property rights, the contents of these rights are defined by the established civil laws and regulations of each member state. Therefore, the Japanese government considers that ownership and other land-use rights, et cetera, that are stipulated in the Declaration, including how they should be exercised, shall be subject to reasonable restrictions in order to reconcile with and protect the rights of third parties and public interests.

(2) Resolution Calling for the Ainu to be Recognized as an Indigenous People.

On June 6, 2008, both chambers of the Japanese National Diet (the House of Representatives and the House of Councillors) passed resolutions calling for the Ainu to be recognized as an Indigenous people, with the following content:

Last September, the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples was adopted by the UN, with the support of Japan, reflecting the long-held aspirations of the Ainu people. At the same time, Japan was called upon by the UN Human Rights Treaty Bodies to take concrete action in accordance with this goal. We must solemnly accept the historical fact that, in the process of Japan’s modernization, many Ainu individuals were discriminated against and forced into poverty, even though they were legally equal citizens.

It is a trend in the international community for all Indigenous peoples to maintain their honor and dignity and to pass on their culture and pride to the next generation, and sharing these international values is essential if Japan is to be an international leader in the 21st century. It is especially significant that the G8 Summit, also known as the Environmental Summit, will be held this July in Hokkaido, the native land of the Ainu people, whose culture is rooted in coexistence with nature.

The government should take this opportunity to take the following measures as soon as possible:

i) Based on the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, the government of Japan should recognize the Ainu people as an Indigenous people of the northern periphery of the Japanese archipelago, particularly Hokkaido, and have their own language, religion, and cultural identity.

ii) Taking adoption of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples as an opportunity, the government of Japan should further promote the Ainu policies that have already been established, and work to establish comprehensive measures, while referring to relevant provisions of the UN Declaration and listening to the opinions of experts at the highest level.

It is hereby resolved.10

(3) Establishment of the Advisory Council on Ainu Policy.

In July of 2008, the Advisory Council on Ainu Policy was established and, in response to a request from the Chief Cabinet Secretary to formulate opinions on the future of Ainu Policy, the Panel compiled a report in July of 2009 that included the following information:

A: That the Ainu are an Indigenous People

The Ainu people were an autonomous group with their own unique culture who lived free from domination or restrictions in the northern part of the Japanese archipelago, especially Hokkaido, since before Japanese rule was extended there. Later, in the process of Japan’s formation as a modern nation, the Ainu people were placed under Japanese rule without regard for their wishes and, as a result of the government’s land and assimilation policies, their connection with nature was broken and opportunities to live a bountiful life narrowed, and they became impoverished. As a result, it became difficult for them to pass on their unique cultural traditions, causing severe damage to their culture. However, even today, Ainu people residing in Hokkaido and other regions maintain their Ainu identity, unique culture, and their desire to revive this culture. For these reasons, the Ainu people can be considered an Indigenous people of the northern part of the Japanese archipelago, especially Hokkaido.

B: On “Respect for Ainu Identity” as One of the Basic Principles of Policy Development

Among the Japanese Constitution’s various human rights-related provisions, Article 13 expresses the fundamental principle of “respect for the individual” which forms the basis of law and order in Japan. If Ainu people affirmatively choose to live with awareness that they belong to a group with a culture that differs from that of many other Japanese (i.e., to possess Ainu identity), this choice should not be unduly interfered with by the state or others. Furthermore, attention should be given to making policies that enable people to live with Ainu identity.

In this light, the state has a clear responsibility to consider measures on the revival of Ainu culture, with especially strong consideration given to policies that promote respect for Ainu spiritual culture and promotion of Ainu language. Moreover, because the Ainu people have deep spiritual and cultural ties to the land as a source of sustenance and place of ceremonies since ancient times, concerted policy consideration is necessary regarding land and resource use, taking the opinions of currently living Ainu individuals and the reality of their livelihood infrastructure11 into account.

Furthermore, the disparity in living conditions and education between Ainu and other Japanese due to historical circumstances is connected to discrimination, which can be considered to have hindered their freedom to live proudly as Ainu. Therefore, measures to eliminate the disparity in living conditions and education should be promoted. This is significant in that it creates the conditions for realizing the intent of Article 13.

In addition, because their existence as an ethnic group is the essential foundation upon which the freedom of individuals to hold Ainu identity is guaranteed, we must recognize the necessity and reasonableness of policy targeting the Ainu as an Indigenous people.

(4) Passage of the Ainu Policy Promotion Act.

The Ainu Policy Promotion Act was adopted in April 2019 and came into effect on May 24 that same year, thereby repealing and replacing the Ainu Cultural Promotion Act (Law No. 52, 1997) (salient fact).

In consideration of the present circumstances of Ainu culture and traditions—which are a source of pride for Ainu persons—along with the international situation concerning Indigenous peoples in recent years, the Ainu Policy Promotion Act recognizes the Ainu people as an Indigenous people of the northern part of the Japanese archipelago, especially Hokkaido, and provides basic principles concerning the promotion of Ainu culture, including that the purpose of the law is to realize a society in which Ainu persons can live with pride and in which that pride is respected (Article 1) and that the aim of the promotion of Ainu policies is to deepen public understanding of Ainu culture and traditions (a source of pride for Ainu persons) and promote the coexistence of diverse peoples and the development of diverse cultures, which are important issues for the international community, including Japan, such that the Ainu people’s pride as an ethnic group will be respected (Article 3). In accordance with these basic principles, the law stipulates the responsibilities of national and local governments to create and implement Ainu policies (Article 5), as well as the contents and procedures associated with such policies.

2. Ainu Livelihoods, Traditions, Culture, et cetera.

(1) Historical Background of the Ainu.

In addition to the contents of 1(3) above (“Establishment of the Advisory Council on Ainu Policy”), in July 2009, the Advisory Council on Ainu Policy summarized the historical background of the Ainu as follows:

A: In the mid-15th century, the Ainu people were trading with Wajin (a historical term referring to people who were considered Japanese at the time, in relation to the Ainu) who had established a base on the Oshima Peninsula.

B: In the Edo period (beginning in 1603), the Matsumae clan was granted exclusive rights to trade with the Ainu by the Shogunate, the newly formed central government of Japan. The area inhabited by Wajin on the southern tip of the Oshima peninsula became known as Wajinchi, while other areas became known as Ezochi (land of barbarians). Ezochi was an area where the Ainu people could live, and Wajin were forbidden to enter or leave the area without permission from the Matsumae clan.

Since rice could not be grown in Ezochi, in lieu of the common tributary system based on rice yields, the Matsumae clan divided the coast of Ezochi among its vassals and gave them the exclusive right to control trade in these areas (called trading posts). These new landlords established themselves in Ainu hunting and fishing areas (known as iwor) that were occupied by various Ainu villages. A landlord would purchase goods that were in high demand by Ainu, such as rice and liquor, from the Japanese mainland and exchange them for products from Ezochi, such as animal skins and dried salmon, which he then sold to merchants who had set up shop at Matsumae Castle. Later, this system came to be called the Trading Post Tribute System. As a result, the Ainu people became increasingly dependent on trade with the Wajin and their incorporation into the broader economy of Japan. At the same time, the Ainu people were forbidden to trade with Wajin with the exception of the ships sent by the landlord to each trading post.