The Vienna World’s Fair of 1873 was a massively important geopolitical opportunity for the fledgling Japanese Empire. Only 19 years earlier, the unexpected arrival of the American Commodore Perry’s fleet to the coast of Kanagawa had forced the Shogun to open the country’s ports to international trade, setting into motion a course of events that would result in the end of the Shogunate and restoration of the Meiji Emperor. Under the new regime, Westernization—the importation of Western technologies, government reform, and a reimaging of the concept of citizenship, among other things—was an issue of paramount importance. But it was not enough that these policies be enacted domestically; to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the so-called Great Powers of Europe, Westernization had to be performed on the great stage of international diplomacy. As Noriko Aso puts it in Public Properties: Museums in Imperial Japan, “The terms—nation state, civilization, commerce, and competition—were set by Western Imperial powers at their world’s fairs.” Thus, Japan’s participation in the 1873 Vienna Exposition should be understood as something of an attempt to ‘fit in’ by modeling statecraft and public exhibition according to the terms set by the European powers.

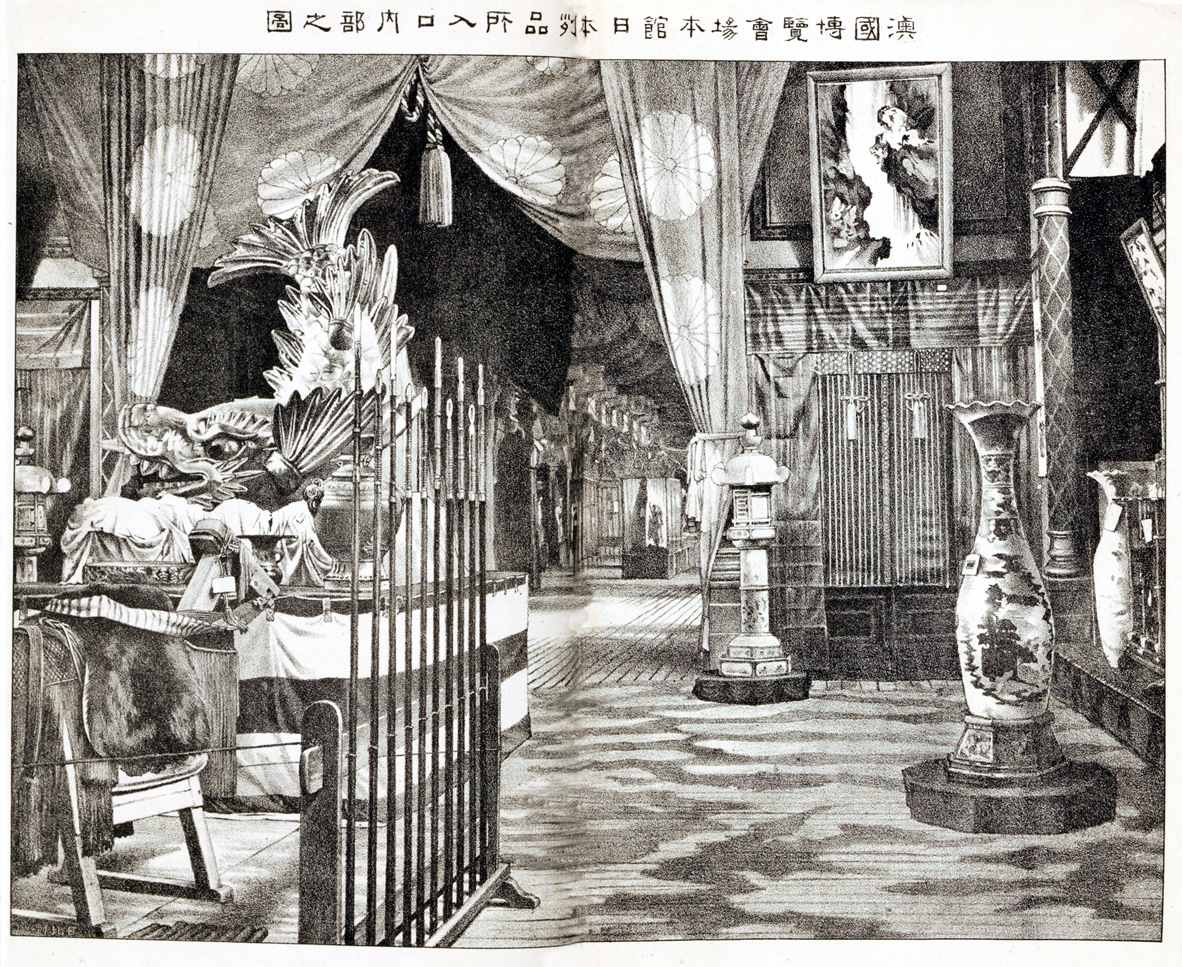

This context, I would argue, is necessary to understand the selection of objects that were ultimately sent from Japan to Vienna in 1873, many of which were exhibited at the Upopoy National Ainu Museum between July and November of 2025 in its 10th Special Exhibition, Ainu Collection at the Vienna World Exposition of 1873. The show was curated as a collaboration between the National Ainu Museum and the Ethnological Museum of Berlin and presented a range of particularly exceptional objects from the world’s fair of more than 150 years ago. These were mostly Ainu objects, though the exhibition also included a selection of Wajin and European materials to give audiences a more complete picture of the 1873 World’s Fair in general and the Japanese pavilion in particular; an elaborately decorated Maki-e vase, ornate European dishware, and Ainu materials ranging from makiri to attush were presented side-by-side in a manner that strikes me as a necessary curatorial intervention. Too often, museums frame Indigenous material culture in purely ethnographic terms while equivalent objects produced by colonial empires are afforded the loftier status of “art.” Ainu Collection at the Vienna World Exposition of 1873 takes steps to redress this museological injustice not only by affording equal stature to the objects themselves, but also by affirming the value of Ainu artistic practices like ita carving and attush weaving as officially-recognized dentō teki kōgeihin, traditional crafts recognized by the Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry for particular cultural and historical significance. In a very real sense, this intervention seems to have been a primary goal of Upopoy’s 10th Special Exhibition. As Kenji Suzuki and Takeshi Yabunaka ask their readership in their introduction to the exhibition’s catalog: “How do we go beyond the stereotypes embedded in the ‘tradition’ of Ainu Culture? … Now is the time to develop solutions to the challenges we face today.”

But there is an obvious difficulty in reclaiming the Ainu collection presented at the 1873 World’s Fair and using it to articulate a new, decolonial vision of Ainu history: If Vienna was a stage upon which Japan could perform Western modernity for a European audience, colonization needs to be understood as an essential element of that performance. While the United States had its western frontier and the European Powers had their overseas territories in Africa and Asia, Japan had Hokkaido, just as it would soon lay claim to further colonies in mainland Asia and Oceania. In their catalog essays, Suzuki and Yabunaka are attentive to this fact: “the materials selected for the World’s Fair by the Expositions Bureau seem to reconstruct an image of the Ainu that emphasizes their ‘uncivilized’ nature,” they write, leaving little room for doubt that the impetus for displaying Ainu materials in Vienna in the first place was to reify the “civilized” nature of the Japanese state through the fabrication of an “uncivilized” Other.

Upopoy’s 10th Special exhibition ultimately attests to a possibility that I find promising—the possibility that even the most fraught archives can offer hints towards the realization of a truly decolonial future. Even so, I also wonder if Ainu Collection at the Vienna World Exposition of 1873 may have left too much of the context behind Japan’s participation in the Vienna World’s Fair unsaid. At what point does archival reimagination come to risk historical revisionism? And what histories—uncomfortable and dark, but ultimately necessary histories—could be papered over in the process? On a more material level, the return of so many treasured objects from Europe to Ainu-moshir for the exhibition, only to have those objects shipped back upon its conclusion, strikes me as a missed opportunity for critical reflection on the ongoing need for repatriation (though it goes without saying that I do not know what conversations about this issue might be underway behind the scenes ).

In the end, I present this critique not as a condemnation of the 10th Special Exhibition, but in recognition of the lofty aspiration of its curators to work against colonial historiography to uncover a story of the Ainu people that cannot be relegated to the margins of a textbook or the side-gallery of a museum or World’s Fair pavilion. It is a difficult task, undoubtedly, but if Upopoy’s curators hold fast to that goal, I will look with optimism to the exhibitions they will present over the next five years.