Ship of Outlaws (Gorotsuki-bune, 1950) is one of the first narrative films featuring Ainu characters. Directed by Kazuo Mori for Daiei Film, the film adapts the much longer novel by Jirō Osaragi. Silent film star Denjirō Ōkōchi plays a samurai disguised as an Ainu man working as a spy for the shogunate during the early 1800s. He is tasked with exposing a smuggling operation in Ezo, the appropriated Ainu lands over which the shogunate has claimed monopoly. The film centers around the illegality of this trade, of the Matsumae samurai abusing their role as appointed officials of the mainland government by dealing contraband goods, violating the government’s strict control over international trade.

As a 1950s jidaigeki (period drama), Ship of Outlaws hits all the right notes. A morally upright samurai battles corrupt and greedy officials, who threaten beautiful women, and clash swords in stunning fight scenes. The plot itself involves multiple characters of dubious ethics and shifting loyalties. If not of complex roles like Omitsu, who poisoned the hero before coming to love him, and the thief, who overhears a plot to kill his former master while robbing him and rushes to warn him, the other characters are villains or lack the ability to protect themselves, like the murdered merchant, his daughter, and the inspector whom the smuggler intended to frame for murder. Omitsu and the thief operate in a realm of moral liminality, while the daughter and the inspector more fully fulfill the role of victims for our hero to protect. In comparison, Denjirō Ōkōchi portrays a forthright character in Mondonoshō Tsuchiya. Interestingly, the one figure who dons a literal disguise to deceive people is also the most righteous one.

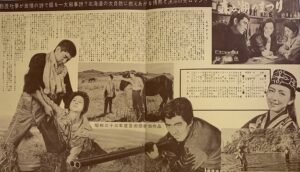

Mori introduces Tsuchiya in the impoverished and downtrodden guise of an Ainu man. We know he is Ainu because the smugglers shout “He’s Ainu!” when they find him. He remains obscured, when they haul him into the open, thrown face first into the sand where we can only make note of his facial hair and Ainu robes. This guise and his vacant body language prompts the smugglers to dismiss him. This disguise, like foliage, hides him. After the smugglers leave, Ōkōchi straightens and shows the true face of Tsuchiya behind his voluminous beard and hair — gaze suddenly direct and steely.

Despite his disguise, Tsuchiya’s moral fortitude is protected by his narrative closeness to the “true” civilization of the capitol, Edo. Ezo, which we know contemporarily as Hokkaidō, provides the story with a sense of remoteness. Mori uses its geographical distance from Edo to imply a parallel distance from lawfulness and civilization. The aristocratic smugglers are of the mainland, being officials appointed by the government, but have been corrupted by Ezo, which produces either villains or victims in the film.

In contrast, Omitsu, played by Chieko Sōma, provides a much more complex role. While Tsuchiya uses Ainu-ness as foliage to hide behind, Omitsu’s connection to Ainu is more concrete, the daughter of an unnamed Ainu woman. Plot-wise, this connection is only important at the end of the film, when she summons a horde of Ainu men to help her and Tsuchiya defeat the smugglers and escape to Edo. This scene reflects the Hollywood, cowboy-and-Indian trope popular in theaters at the time. In a twist of the classic Western formula where the lone gunslinger must repel his attackers, here, the “natives” come to the aid of the government-aligned hero. Ainu people are not antagonists but rather tools for the hero’s use. Although Omitsu is disparaged once for her heritage by one of the villains, her Ainu-ness is not highlighted inside the narrative except for this use. Nevertheless, her position as a daughter of an Ainu woman (she is not herself directly called Ainu) provides her character with a sense of ambivalence.

Unlike nearly all the other characters that belong to Ezo, Omitsu is neither wholly a victim nor a villain. She poisons Tsuchiya, but witnessing his moral fortitude, she nearly immediately regrets her action. Despite Tsuchiya’s later rejection, she finally proves herself by risking her life to protect the merchant’s daughter (whom Tsuchiya needs as a murder witness). Not simply an act of loyalty, her actions prove her moral fortitude and therefore seems to align her with the values of the capitol and “civilization” in the story. While the merchant’s daughter has no power and lacks the ability to protect herself, Omitsu’s agency in the narrative prevents her from wholly being a victim. Her agency relies on her ability to cross boundaries. The Matsumae aristocrats do not accept her due to her heritage, but she is also set on the periphery of Ainu activities, connected but distanced.

The film is certainly not meant to explore the ambiguity of belonging at the periphery of the Japanese nation. More so, the film shows how deeply filmmakers associated Ainu culture and characters with the background of Hokkaidō. The right of the shogunate to apply their own trade policies to land taken from Ainu people is treated as given. Edo’s shadow, its power, looms over the story, the epicenter of moral value. Ship of Outlaws follows the standard jidaigeki formula of the 1950s, especially before censorship was lifted in 1954 — hidden government officials, spectacular fights scenes that uplifted the hero, and clear distinctions between good and bad. Ainu presence, images tightly linked with Hokkaidō itself, was made to fit into this story-mold. Omitsu’s liminality and agency may not undermine the film’s colonial hierarchy, but they certainly stand out, and presents a more variable look at how filmmakers used Ainu-ness on screen.