The opening of Mori to Mizūmi no Matsuri (1958) could easily be mistaken for a Hollywood western. The camera performs a long pan over rugged mountains and grassy plains, from which we watch Kazamori Ichitarō ride into view, like the now iconic cowboy. Director Uchida Tomu places us on the shores of Lake Tōro in Shibecha, southeastern Hokkaidō. Mori to Mizūmi no Matsuri, meaning Festival of the Forest and Lake, alludes to the pekampe kamuynomi, an autumnal celebration when local Ainu would row out together onto to the lake, collect the floating pekampe (water caltrops), and thank the kamuy (often translated as gods or spirits) for the harvest. The film popularized the festival, drawing crowds of tourists before the last celebration, held in 1990. The history of the pekampe kamuynomi, as well as posters and scripts from Uchida’s film, are memorialized in the Nitay-To (Forest Lake) Shibecha Museum, est. 2018, off Lake Tōro where pekampe, black and spiky, still wash ashore. It is important to note that despite this titular emphasis, the festival itself hardly appears on screen. The festival acts as an invisible focal point, occurring in the distance as the film’s most important events unfold. The festival’s lack of visibility is especially notable when considering the film’s English name. Not a direct translation, The Outsiders is a title that emphasizes the film’s complicated portrayal of ethnic belonging, where every character, both Ainu and wajin (Japanese ethnic majority), is in some way othered by an invisible center.

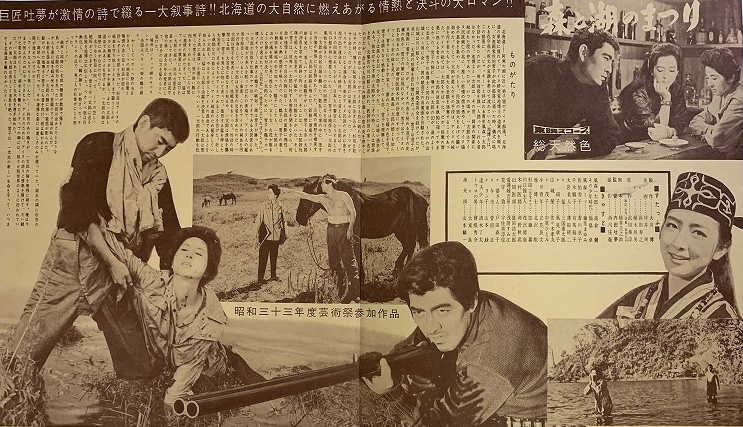

Uchida articulates discrimination in multiple ways. He filmed Mori to Mizūmi no Matsuri before the social protests of the 1970s, before the Ainu Liberation League began denouncing the way Ainu were represented in media, and before actors within the New Left movement began appropriating Ainu discourse to commit political violence. Kazamori, also called Byakki (Phoenix), is played by the thorny, masculine icon Takakura Ken. Uchida Tomu immediately presents him as a folk hero, wandering the land to disperse gifts to village children. However, as the story continues, the freedom and independence the opening scenes originally evoke begin to warp. Although the film begins (and ends) with Takakura’s character, the story’s main narrator is actually Yukiko, a wajin painter from Tokyo played by legendary actress Kagawa Kyōko. Through her and her growing feelings for Kazamori, we discover Kazamori as a violent Ainu rebel, fanatical in his devotion to protect Ainu from vanishing. In hindsight, Takakura’s character shows a fear of what Ainu rebellion could look like — angry, destructive, and self-annihilating. The film, in many ways, is exemplary in its strong indictment of discrimination against Ainu, strongly critical of anthropological gazes, and the only film that shows a wajin woman sexually interested in an Ainu man. However, it still treats assimilation as inevitable, and resistance as destructively violent. Yukiko is an ignorant voyeur. So focused on trying to capture “Ainu skin” in her paintings, she fails to see how predatory and objectifying her gaze is. The dialogue classifies her behavior as “insensitive” (mushinkei), coming more from a place of self-centeredness than racial discrimination. In this way, Yukiko’s ignorance may represent the audience’s ignorance, or Uchida’s, and of any outsider trying to depict Ainu for their own artistic merit. Once confronted, her shame is immediate, and this shift allows the film to move past surface-level observation and hear the deeper, more complicated stories that the Ainu characters tell.

Takakura Ken’s character is only one of several Ainu figures, each with their own experience being othered. However, Kazamori and his anger is sharply contrasted by his sister Mitsu. Mitsu reveals to Yukiko in flashbacks that she had fallen in love with an older wajin teacher when she and her brother were young. The teacher Sugita had sheltered them from the police. During the pekampe kamuynomi, Sugita breaks their engagement, fearing the prejudice he would incur for marrying an Ainu woman. In anger, Mitsu convinces her brother to kill Sugita. They both change their minds, but the incident causes Mitsu to convert to Christianity, and focus on forgiveness, and Kazamori to lead a one-man rebellion for a righteous but ambiguous Ainu cause. Sugita has since fallen into drink after breaking his engagement with Mitsu. Miserable, he approaches her in the hospital. Mitsu forgives him as quickly as she forgave Yukiko her predatory voyeurism. Certainly, if Kazamori represents hostility towards prejudice, Yukiko represents its passive forgiveness. Just as their romance seems rekindled, Kazamori appears. Considering Sugita has already abandoned her once, Kazamori has good reason to oppose their relationship. However, the friction here is unquestionably ethnic. There conversation resolves not around Sugita’s relationship with Mitsu but on the fate (unmei) of the Ainu. Sugita claims that the destruction (horobu) of the Ainu is inevitable. The Ainu inside the village think so too, he claims. “If you do not mix, who will be left?” he asks. Kazamori rejects him, determined to play the role of the hero (jiinketsu).

As it was during the festival when Sugita broke his engagement with Mitsu, it is during the festival when Kazamori has the film’s final showdown, a gunfight with another Ainu character Oiwa. Despite being Ainu himself, Oiwa, the manager of the local fish-canning plant, refuses to hire Ainu workers. The duel results in buckshot scattering against Kazamori’s face. Strikingly, shortly after it is revealed that Kazamori is actually half-wajin, his face is destroyed. The festival represents both culture and tradition, and the Ainu characters are constantly pulled away from it. Kazamori seems to have no connection to it at all. His hostility and violence all point towards preserving Ainu culture, but he himself does not engage with it. His relationship to culture is warped. Oiwa even calls their duel and his rifle a charanke, traditionally a method of debate used to resolve conflict.